Filters can cut the volume of ocean-bound microplastic fibres released by washing machines, a study has shown.

However, until now, filters have not been tested under scientific conditions to prove their effectiveness.

In the first study of its kind, scientists found that the majority of fibres were removed but up to a third were still getting through.

Each year, an estimated 50 billion garments are washed in machines around the globe.

Mark Browne from the University of New South Wales, and colleagues Macarena Ros and Emma Johnston, observed: "Facilities that treat sewage divert some fibres to sludge, but no current method of filtration eliminates their environmental release."

One possible solution was to stop the release of the microfibres from washing machines by using commercially available filters.

However, the team found that there was "insufficient scientific peer-reviewed evidence assessing their ability to retain fibres from washed clothes".

Invisible plastic tide

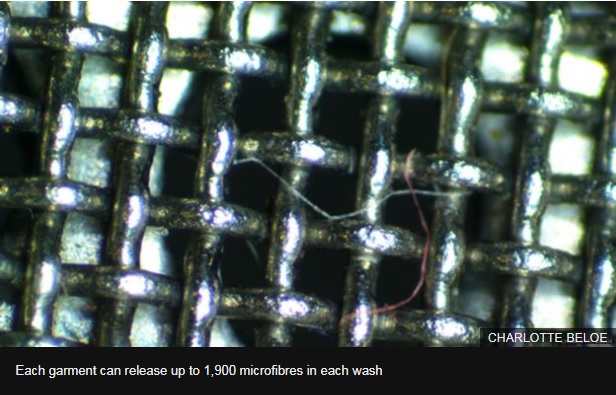

In 2011, Dr Browne and his team showed that when clothes were worn and washed, they were releasing up to 1,900 fibres during each wash.

In order to understand how the filters performed, the team set up an experiment to test the effectiveness of the devices.

"We washed replicate cotton and polyester garments in replicate domestic front-loaded washing-machines with and without replicate filters (micro- and millimetre-sized pores)," Dr Browne explained.

"[We] then quantified the masses of the fibres retained by the filters and those released in the effluent."

The team found that the filters "significantly reduced" the amount of cotton and polyester fibres in the effluent, up to 74%, compared with effluent from appliances with no filters.

However, a sizeable proportion of the microfibres were still eluding the filtration systems, the team found.

Dr Browne observed: "Given the diversity of clothes, polymers, appliances and filters currently sold to consumers, our work shows the value of increasing the rigour (e.g. more levels of replication) when testing filters."

He added that the study showed that there was a "need for further studies that test an even greater diversity of materials and methods in order to meet the growing demand for knowledge from governments, industry and the public".

Rising tide

In recent years, the question of plastic waste entering our seas and oceans has dominated headlines and has become one of the most pressing environmental issues.

Each year, an estimated 150 million tonnes of plastic is "lost" from waste streams, meaning it is ending up in the wider environment.

While plastic bottles and plastic bags have been recognised as harmful to organisms and the environment, there is a growing body of evidence that suggests that so-called microplastic - pieces of the synthetic material measuring 0.5mm or smaller - is entering food chains and altering the cellular structure of organisms.

Dr Browne, in a 2013 study, found that these tiny bits of plastic were being ingested by lugworms.

The organisms are described as eco-engineers as they eat organic matter on shorelines, preventing the build-up of silt on beaches or river systems.

However, if they have digested plastic into their guts, the worms will not be able to eat as much organic matter, which in turn affects the local ecosystem.

Also, the study showed, the microplastic absorbed toxic material, such as fire retardants. If enough was digested, this could also affect the worms.

Dr Browne said developing products, such as filtration systems, using scientific evidence would deliver better environmental protection and greater consumer confidence.

"We urgently require information from robust scientific experiments to determine the capacity of technological solutions to reduce emissions of fibres to sewage that range in size from mili-, micro-, and nanometres."