One of nature's smelliest secrets may have been revealed, thanks to a dedicated team of durian-loving scientists in Singapore.

Researchers have found an odour gene which gives the thorny fruit its notoriously pungent scent.

The discovery meant the possibility of creating "odourless or milder-tasting" fruits in future, the scientists said.

It has sparked mixed feelings from durian aficionados, who worship its signature rank smell.

"A durian without its smell is nothing but an empty shell with no essence," wrote Singaporean Richie Liang on Facebook, who also compared "a durian without its unique smell" to "a human being who has lost his or her soul".

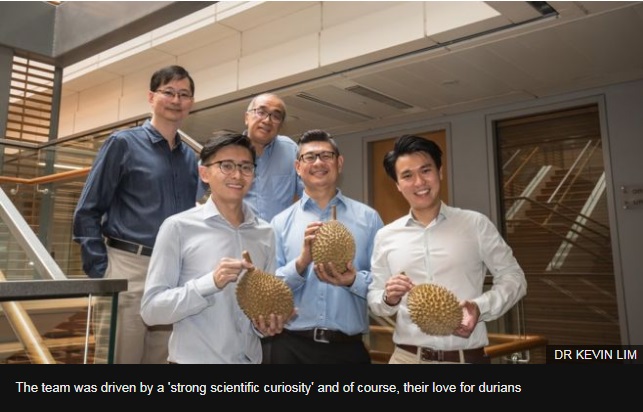

After three years of research, privately funded by a group of anonymous durian lovers, the five-man team of cancer scientists now have a complete genetic map of the fruit, a world first.

Their findings were published in academic journal Nature Genetics.

"Our analysis revealed that volatile sulphur production is turbocharged in durians, which fits with many people's opinions that durian smell has a 'sulphury' aspect," said geneticist Patrick Tan, who co-led the study.

The researchers said the durian's distinctive odour served an important purpose to it in the wild: helping to attract animals to eat it and disperse its seeds.

Grown in many countries across tropical South East Asia, the spiky, stinky durian is an acquired taste.

The fruit is loved and loathed in equal measure. Eating durian is banned in many outdoor spaces throughout Singapore and carrying it is prohibited on public transport because of its smell.

But its fans remain fiercely protective over retaining its controversial scent.

"What's durian if it's odourless and tasteless? Yuck," said Manfred Man, adding that he would "never mess with nature".

Jason Lim saw the potential in the durian discovery and shared his hope for new hybrid signature smells. "I wish someone would create avocado with durian smell. Durian fans will know what I am talking about."

Odours aside, the durian's ancestry was also revealed, believed to be dating back an estimated 65m years to the cacao plant.

Zachary Tay hilariously summed up this revelation: "So we're basically eating chocolate."