David Liu, a Chinese Frenchman, says he walks around Paris with "fear in his chest".

The 22-year-old student was assaulted and robbed by a gang of youths in a side street when he was in primary school.

It was a long time ago, but he still crosses the road if a large group of people are coming his way. After all, everyone in his family has been targeted in a similar fashion.

France's ethnic Chinese population have long suffered casual racism and been stereotyped as easy targets for crime. But they say they have now reached breaking point.

In August, 49-year-old tailor and father-of-two Zhang Chaolin died in hospital after being attacked by three teenagers. He had been walking in a quiet street in the north Paris suburb of Aubervilliers.

Zhang was reportedly kicked in the sternum and fell, striking his head on the pavement. The aim of the attack was allegedly to steal his friend's bag.

The tailor had nothing on him except sweets and cigarettes.

In response, on 4 September, at least 15,000 ethnic Chinese turned out in Paris's Place de la Republique to give vent to their deep feelings of insecurity.

Estimated at more than 600,000 people, France has Europe's largest Chinese community. But they have not been in the country as long as more prominent migrant groups, including those from Africa.

David was born in Paris to parents who migrated from China in the early 1990s. He says he has been asked publicly if he eats dogs, and has been called a "spring roll head".

He has also been told to "go back to his own country" and "go and work with his little Chinese hands".

Such jibes might be familiar to east Asian migrants and their descendants across the West. As with British Chinese, French Chinese say that racist comments toward them are tolerated, in a way that they are not for more established migrant communities.

But in France, there is a sense that Asian migrants are targeted with particularly nasty violence.

"[These attacks] are because of the beliefs they have about us," says David, who is too fearful to use his real name.

'Weak and cashed-up'

A working-class and immigrant-heavy area, home to more than 1,200 mostly Chinese wholesalers, Aubervilliers is an important European textile centre. Buyers come from far and wide to haggle over Italian-made coats and Chinese-made shirts.

Activists say at least 100 attacks against Chinese nationals were reported in the suburb in just the first seven months of this year. France does not keep statistics based on ethnicity, so it is difficult to know the real number of incidents.

Meriem Derkaoui, the suburb's communist mayor, condemned Zhang's murder as "racist targeting".

Community groups say such attacks are driven by a perception that Chinese people are weak, will not fight back and carry a lot of cash.

During a recent trial of three youths accused of 11 attacks in a three-month span in Aubervilliers, the defendants insisted the ethnicity of their targets was just a coincidence. But when interrogated by police, they reportedly admitted to seeing Chinese people as "easy targets" with money on them.

In interviews with the BBC, several ethnic Chinese shopkeepers and residents of Aubervilliers said they felt that the level of violence was getting worse.

"It's getting out hand. The situation had stabilised in recent years, but now it's broken out again," says Franky Song, 20, who works in a jeans shop in the CIFA Fashion Business Center. Inter-communal relations in the area have deteriorated, he adds.

In this shopping centre, home to a few hundred clothing wholesalers, everyone would know someone who had been assaulted, he said. "We have the businesses, but not the build, so they take advantage of us."

Heng, a middle-aged lady who has run a florist's with her husband in Aubervilliers for 17 years, joined the recent protests because of the "horrible situation" in the suburb. Her shop has been broken into twice, and her insurer will no longer cover it.

The anger of people like Franky and Heng is mostly directed towards the state, which they say has failed to protect them. Zhang's death was the final straw. It prompted a community normally regarded as quietly focused on work and family to take a public stand.

'We've had enough'

"Asian people are not used to being in the spotlight; they like to be in the shadows," says Frederic Chau, a well-known comedian and actor of Cambodian-Chinese descent. He has played a high-profile role in the "Safety for All" campaign, which previously organised demonstrations in 2010 and 2011.

"To be more than 20,000 people in the Place de la Republique to make this protest - it's not normal, for us, [especially] for my mother, my father, my uncles.

"But doing this is necessary because we have had enough. We have to do something to change the mentality in France."

As one of the Indochinese refugees who arrived in France in the 1970s with the legal right to residence, Frederic is part of an ethnic Chinese community considered better integrated in French society than their mainland Chinese counterparts.

France's colonial history meant that some of these refugees from Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia - many, like Frederic, of Chinese descent - already spoke French.

The Chinese wholesale trade in Aubervilliers, on the other hand, is dominated by migrants from Wenzhou, a city in China's southeast known for its entrepreneurial migrants. They mostly arrived in the late 1980s and early 1990s, with the first generation struggling with the French language.

Ya-Han Chuang researched the integration of Chinese migrants for her doctorate at Paris-Sorbonne University. She says that compared to the Indochinese, these mainland migrants have struggled to accrue "cultural capital".

"The fact that they tend to work in and inherit family enterprises creates some more barriers," she says.

But Rui Wang, the son of Wenzhounese migrants and president of the Association of French-Chinese Youth, belies the stereotypes.

Born in China but raised in France, he casually quotes French philosophers and sociologists like Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Pierre Bourdieu. Articulate and driven, he has written to Prime Minister Manuel Valls to warn him that the situation in places like Aubervilliers is "explosive".

He describes how husbands will pick up their wives and children from metro stations and schools in groups of five to six people for safety reasons.

In La Courneuve, near Aubervilliers, look-outs are posted near weddings to prevent robberies. Security information and patrols are coordinated via the WeChat messaging app.

"There is an anger that has accumulated for too long," Rui says.

The association's immediate demands are straightforward: more police and security resources. Since the demonstrations in August and September, extra police officers have been promised for Aubervilliers. But according to Rui, city hall says it cannot afford to provide more security cameras.

The mayor did not respond to requests for comment on these issues.

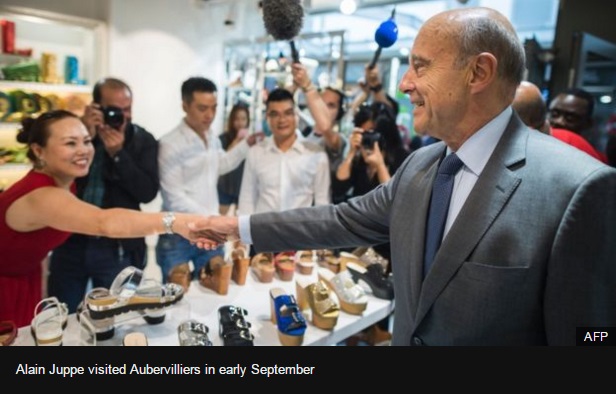

The recent protests have captured rare media and political attention for a community unused to the limelight. Alain Juppe, a former prime minister and likely presidential candidate, visited the family of Zhang Chaolin in early September.

Speaking to French-Chinese in the area, he condemned rising incidents of "anti-Chinese racism" and spoke of France "finding harmony between its communities".

This is equally important for Rui. He wants more support from the government for social projects that build links between different migrant communities.

Frederic Chau, the actor, feels the same way. He describes his family home's doormat as being like a border between France and China when he was growing up: "I rejected my origins, I wanted to be whiter than white".

Now, he has fully embraced his Cambodian and Chinese origins, and is proud of them.

What France's Asians want now, Frederic says, is to be "considered French".

When perceptions change, they hope a sense of security will follow.