Are Disney princesses the best role models for little girls? The frequently asked question has come up again, sparked by two linguists and their new study.

Carmen Fought, a professor at Pitzer College in Claremont, Calif., and Karen Eisenhauer, a graduate teaching assistant at North Carolina State University, have gathered up all the dialogue from Disney’s decades of princess movies and discovered something interesting: The oldest of the films, dating back to Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937, give more speaking time to female characters than male ones (as also reported in The Washington Post). This is in deep contrast with Disney’s newer classics, including The Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast, wherein women characters speak markedly less than men.

“I was struck by how some critics or social science researchers would say that Ariel or Pocohantas was a great role model, and others would say that character was awful for little girls to see,” Fought told Yahoo Movies. “But neither side really seemed to support their arguments with data.” That’s when she and Eisenhauer set out to “bring some objectivity to the analysis.”

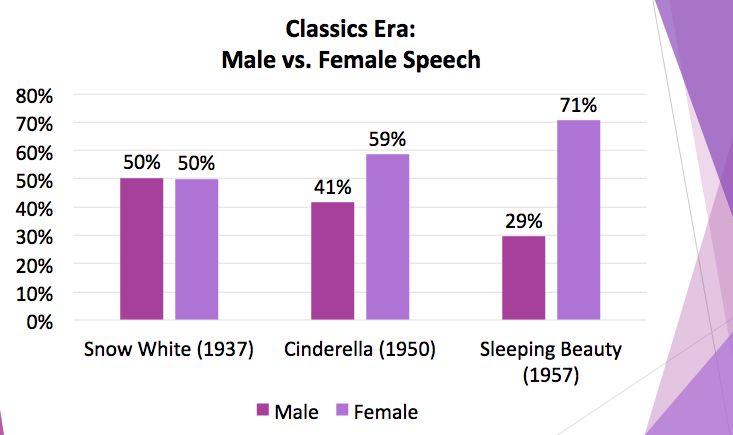

Still in the early stages of the study, the two linguists want to shed light on how male and female characters speak differently in the set of Disney animated features. In the first three princess movies by the studio — Snow White, Cinderella, and Sleeping Beauty — women characters speak as much or more than their male counterparts. Sleeping Beauty is the most extreme example, where women characters talk 71 percent of the time.

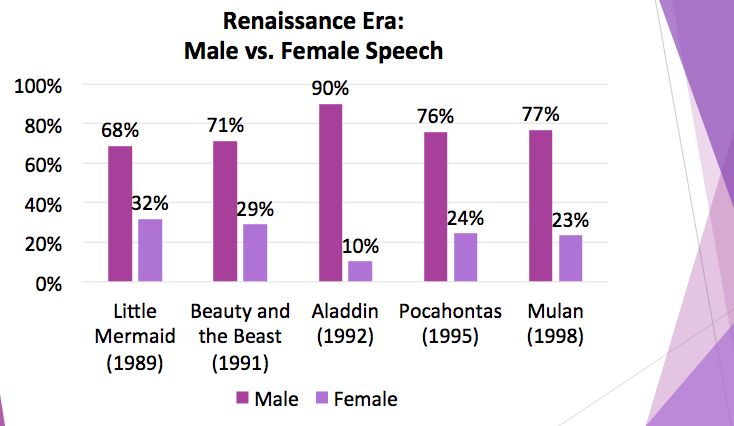

Disney’s so-called Renaissance-era films, starting with 1989’s Little Mermaid and ending with 1998’s Mulan, had a much different result — none came close to the 50 percent mark when it came to female dialogue. The worst offender: Aladdin, which allowed only 10 percent speaking time to its female characters.

Fought told Yahoo Movies that part of problem is that most of the characters in all Disney princess films are male. “It represents a cultural default to assign any unmarked roles to males,” she said, pointing out that there are more male roles in Snow White, even though half its speaking time goes to women characters. One key example can be taken from Disney’s Renaissance-era princess films: Almost all of the comedic sidekick roles are assigned male: Sebastian, Flounder, Lumiere, Cogsworth, Iago, Genie, and Mushu. The only break from that trend was Mrs. Potts, voiced by Angela Lansbury in Beauty and the Beast.

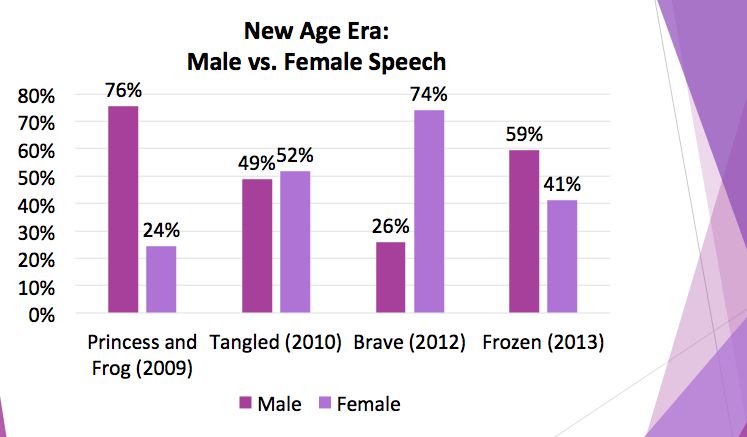

Disney took a 10-year break from princess movies following 1998’s Mulan, and the ratio of lines uttered by women improved in some titles but not in others. 2012’s Brave intentionally set out to break the princess mold with its fiery, feminist Merida. But you might be surprised to learn Disney’s monster hit Frozen, starring two female leads, mind you, gave female characters only 41 percent of the film’s dialogue. “Minor roles seem to go to men,” Fought reiterated. “This doesn’t mean the movie couldn’t have progressive, even feminist, aspects. It just means that in this way, women’s voices are still given less air time than men’s voices.”

Fought and Eisenhauer also counted up onscreen compliments received by females in all of the Disney princess movies and found progress has been made. “Women are being more often complimented on their skills versus their looks,” Fought said of an overall trend revealed in her study. And that’s an important stat, she says, because studies have revealed that even “complimenting women on their appearance can cause a positive feeling but also an increase in body shame.”

Next up, the two linguists are collecting data on Pixar movies, including Toy Story. “There are not a whole lot of females in that [film] either,” said Fought. “I hope others will expand our work to other genres.”